My research into the Great War has led me all over the place, some —ok, most— of the time to areas which will be completely irrelevant to my novel. Nevertheless, these forays into the history of the war have uncovered so many interesting and intriguing stories that I’m loath to shift my focus onto the more useful information for the novel. This is exactly what happened when I did a teeny, tiny bit of reading on The Red Baron for my drawing challenge this week. Of course I already knew the basics: German flying ace, noble family, bright red aircraft, killed in the final stages of the war. But there’s so much more to this fascinating character’s story. And no, it has nothing to do with Snoopy.

The second of four children and the oldest son, Manfred von Richthofen was born on May 2, 1892 near Breslau, in Lower Silesia. This region later became part of Poland after borders shifted back and forth during the two world wars. The von Richthofens were an aristocratic Prussian family, with the noble title ‘freiherr’, often translated as ‘baron’ but literally meaning ‘free lord’, applying to all male family members, even while the father was still alive. Thus Manfred and his two brothers, Lothar and Bolko were all ‘barons’ simultaneously with their father, Major Albrecht Philipp Karl Julius Freiherr von Richthofen.

Manfred’s early years were active and outdoorsy. After being educated at home, he began his military training at age eleven. His cadet training was completed in 1911 and he subsequently joined a cavalry unit in one of the West Prussian regiments. After the outbreak of war, von Richthofen served as a cavalry reconnaissance officer for the German army, seeing action not just on the Western Front in France and Belgium, but also on the Eastern Front in Russia. The nature of trench warfare made traditional cavalry operations near impossible and so after a short while, von Richthofen’s unit was removed from horseback and employed running dispatches and operating field telephone communication. Manfred found this boring and dissatisfying work and yearned for a more active role in combat operations. And so, his interest aroused after seeing the wreck of an enemy airplane behind the lines, he decided to apply for transfer to the Imperial German Army Air Service, later known as the Luftstreitkräfte.

His early piloting attempts were less than impressive; he crashed on his first try at flying, but he was determined and inspired to succeed by the likes of German flying ace, Oswald Boelcke. Over the course of his career, Manfred von Richthofen would score the highest number of victories: 80 planes shot down, more than any other pilot in the air services of the combatant nations.

Though he is most closely associated with the celebrated Fokker DR. I triplane, von Richthofen flew several types of planes over the course of the war: the Albatross C III, the Albatross D II, Halberstadt D II, and Albatross D III. And in fact, it was the Albatross D III that was first painted in his trademark red. The bright red color of the plane with the family title ‘freiherr’ combined to yield his nickname: The Red Baron. Despite the obvious risk in painting a plane a bright and distinctive color, the German command allowed it, even using the “Red Fighter Pilot” as a tool for propaganda.

The Red Baron was not invulnerable to attack, however. He was seriously wounded in combat in July of 1917, managing to pull his plane out of a spin at the last minute and force land in a field behind German lines. The injury he received to his head required several surgeries to remove bone splinters and is thought to have caused permanent damage. Changes in his temperament were noted as well as headaches and post-flight nausea. It has even been suggested that this injury contributed to his eventual demise.

On the 21st of April, 1918, Manfred von Richthofen flew to the rescue of his cousin, Lt. Wolfram von Richthofen, who was being fired upon by Canadian pilot, Lt. Wilfred May in his Sopwith Camel. The Red Baron fired on May and pursued him as he fled across the Somme. He was engaged by another Canadian pilot, Captain Arthur “Roy” Brown, causing him to turn to avoid the shots, after which he resumed his pursuit of May. It is during this time that the question and unresolved mystery of who killed the Red Baron arises. Manfred was shot by a single bullet, damaging his heart and lungs. Despite this fatal wound, he retained enough control to land his aircraft in a field just north of Vaux-sur-Somme, behind enemy lines. The Australian forces controlling that sector rushed to the downed plane in time to hear The Red Baron’s last words. Though the reports differ slightly, he apparently said some version of “kaputt.” The Fokker DR. I was not badly damaged in the landing but was quickly harvested by souvenir hunters.

As for the person responsible for taking down The Red Baron, initially the credit was given to Captain Brown for shooting him down. This was later questioned because of the direction from which the fatal shot was fired. The bullet entered beneath von Richthofen’s right armpit and exited near the left nipple. At the time of the shooting Brown was above and to the left of The Red Baron’s plane, an impossible position to have caused that wound. More likely, the wound came from anti-aircraft guns on the ground.

One –and probably the best– candidate for the man responsible for the demise of The Red Baron is Sergeant Cedric Popkin, a machine gunner with the Australian 24th Machine Gun Company. He fired twice at The Red Baron, once as the plane was flying straight at his position and a second time, from the right and at long range. It is this second shot that likely proved fatal to the flying ace.

Still, the questions remain about The Red Baron’s actions that day. His normally prudent behavior in flying combat missions seems to have been thrown to the winds. Could the earlier head injury have impaired his judgement? He flew too low over enemy territory and he flew too fast for safety. Both behaviors were uncharacteristic in the flying ace. Perhaps the combination of the injury, post-traumatic stress (combat fatigue) and the desperation for wins in those waning days of the war all contributed to the recklessness of that final flight.

Whatever the case, The Red Baron was so respected by his enemies that the Australian officer in charge of the burial gave Manfred von Richthofen a full military funeral with members of Number 3 Squadron AFC acting as pall bearers and a guard of honor. The Red Baron was laid to rest in a small village cemetery near Amiens and afterwards members of the Allied squadrons stationed nearby brought memorial wreaths to the grave to honor “Our Gallant and Worthy Foe.”

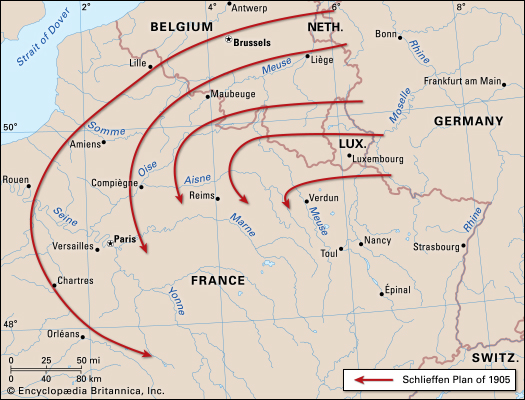

The bulk of the plan had already been formulated by 1895. Minor modifications and what can only be called tampering, were the only changes that were made to the plan after Shclieffen’s retirement.

The bulk of the plan had already been formulated by 1895. Minor modifications and what can only be called tampering, were the only changes that were made to the plan after Shclieffen’s retirement.