In the course of researching for my historical novel (in progress) I began reading about the War Poets: men whose experiences in the Great War gave rise to some of the most moving and heart wrenching poetry ever written. Unlike historical accounts with facts and statistics, the poetry brought to life (and death) the true suffering the men experienced during this dreadful conflict.

Robert Graves was a close friend of Siegfried Sassoon and like Sassoon used his experiences in the war as material for his poetry. He was badly wounded at The Battle of the Somme in 1917 and in addition, suffered the accompanying nightmare of shell shock. Nevertheless, unlike his friend Sassoon, he was never hospitalized for the condition. The story of his journey home, however, includes an odd series of coincidences both good and bad, that make for quite the interesting tale.

After the war, Robert Graves awaited demobilization while on leave in Ireland. For many men, the epidemic flu was hindering the process of returning them to their families. In February 1919, Graves finally received a telegram from the War Office confirming that his papers had come through. In order for the paperwork to be completed, however, Graves needed to return to the demobilization camp near his parents’ home in South London. Unfortunately for him, the release of troops from Ireland was about to be suspended due to the ‘Troubles’.

To make matters worse, he began to experience the intial symptoms of the deadly flu. Fearing for his health, should he be quarantined in an Irish hospital, Graves decided to make a run for it. He convinced an orderly sergeant to make out his travel papers and hopped on the next train from Limerick, even though he didn’t have the proper demobilization code marks. According to his memoir, Goodbye to All That, he said, “…I would at least have my flu out in an English and not an Irish hospital.”

On the night of February 13, 1919, he boarded the ferry to Fishguard with a high fever. He reports still having his mental faculties in good form, however. So upon discovering that a strike on the London Electric Railway was imminent, Graves immediately boarded a train from Wales to Paddington, in hopes of outrunning the inevitable disruptions. He made it safely and was able to catch the connecting trains and arrive at his home in Hove before travel was suspended. Another happy accident was that he found himself sharing a taxi with a soldier who just happened to be the Cork District Demobilization Officer and was willing to provide him with the final code marks he needed to complete his paperwork.

The bad news: upon arriving at his home, he was so ill that he immediately took to his bed. And though Graves himself recovered, within two days of his return home, everyone in his household was dead except for his father-in-law and a servant.

Here is one of his poems:

The Last Post (June 1916)

The bugler sent a call of high romance–

‘Lights out! Lights out!’ To the deserted square:

On the thin brazen notes he threw a prayer,

‘God, if this is for me in time in France…

O spare the phantom bugle as I lie

Dead in gas and smoke and roar of guns,

Dead in a row with other broken ones,

Lying so stiff and still under sky,

Jolly young Fusiliers, too good to die.’

The music ceased, and the red sunset flare

Was blood about his head as he stood there.

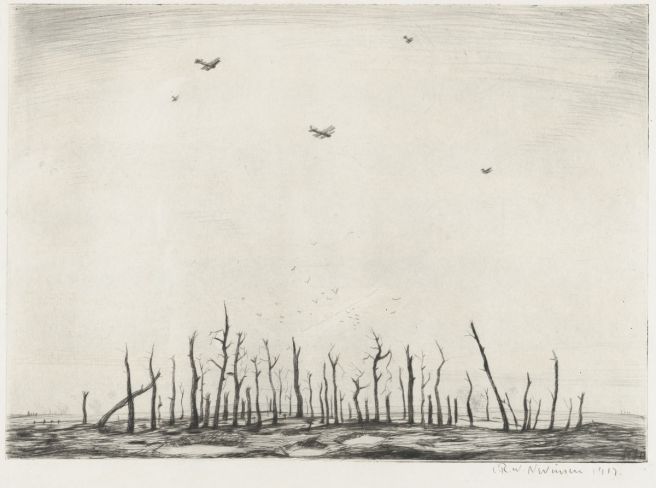

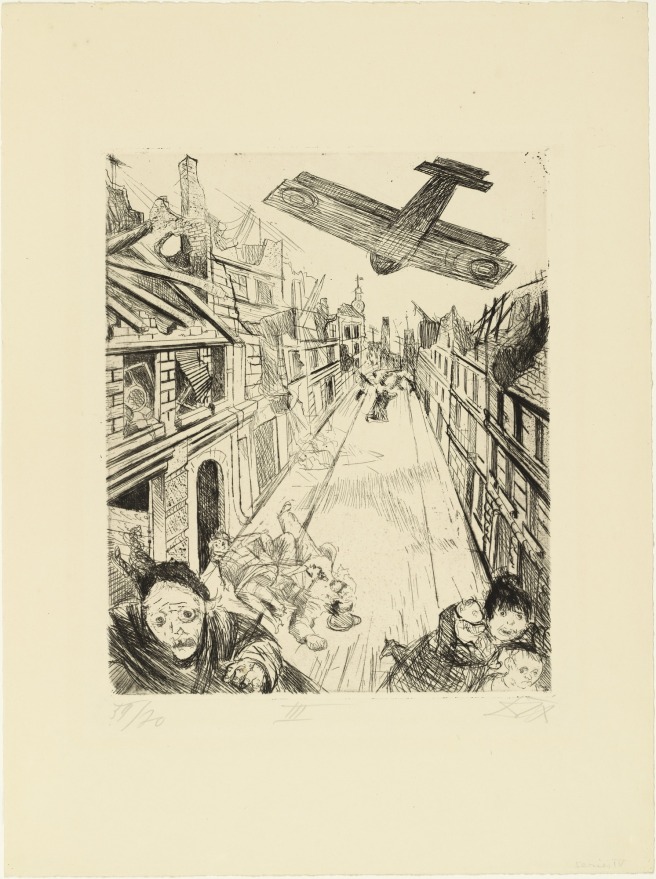

Image courtesy Australian War Memorial